Dr Aileen Ireland, Research Fellow, University of Stirling

27 October, 2020

As every part of the education sector comes to grips with the effects of COVID-19, each organisation has had to adopt creative ways in which to govern their responses to this disruption. Along with many other organisations, governance of further education has moved to online spaces; not only to respond to the complex unpredictability of constantly shifting health regulations, but also to attend to the usual routine governance of further education institutions. As such, the processes and practices of FE governance have undergone a radical shift in adjusting to the ‘new normal’.

Our project, funded by the ESRC, explores the processes and practices of governing in further education colleges in the four countries of the UK, focusing closely on how they ‘do’ governing. Throughout 2019, we observed meetings of the board of governors of eight FE colleges and conducted interviews with key board members.

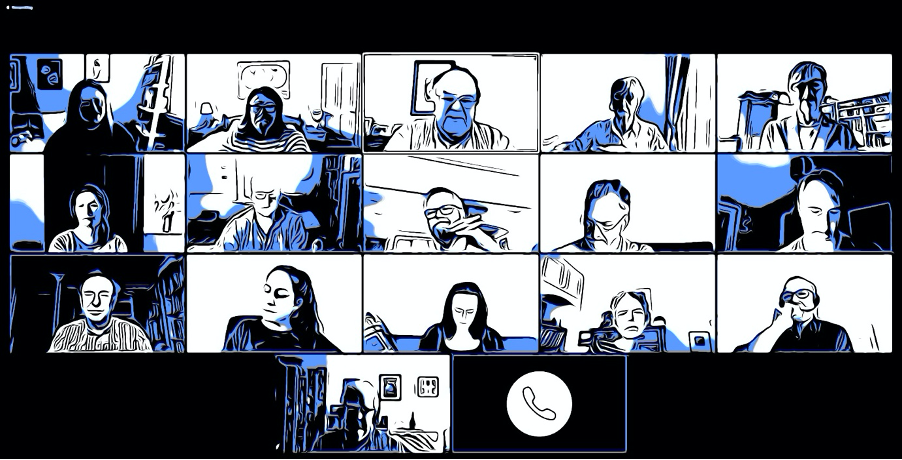

Over the past few months, the research team has been privileged to observe online meetings in several of our partner colleges. The shift to meeting online has provided us with a unique opportunity to explore how the processes and practices of governing have changed in the move to online spaces – to explore how boards continue to conduct the processes that underpin the construction of ‘strategic aims’, ‘outcomes’ and ‘quality of provision’ while grappling with the uncertainties that the pandemic has presented.

Part of this challenge has included the governors having to contend with new technologies as well as new ways of ensuring that the regulated processes of governance are being upheld. Because we have a wealth of observations of what constitutes ‘boards in action’ before the pandemic hit, we are in a good position to consider how these new online technologies and ways of working are mediating the governance of FE. In addition, as our own research practices have moved online, we have engaged in several interactive webinars with our project ‘Impact Group’ – an advisory group including representatives from our participating colleges and key organisations across the UK –providing further materials to inform how online video meeting technology has influenced FE governing practices.

Our early analysis shows that boards have adapted well to the online video meeting platforms, with most utilising the built-in functions to ensure that the meetings run smoothly. Many boards note that, by moving their meetings online, they have much better attendance, and that the meetings are shorter and issues are addressed more quickly. Indeed, in our observations, Chairs tended to move quickly through the formalities of checking previous minutes etc. so that they could focus on issues related to how COVID-19 has changed and challenged college operations and management. Some governors expressed that they felt the online meetings were more ‘business-focused’.

Some examples of changes in practice include an increase in the number of meetings between committee chairs to provide more frequent updates to board members, and the setting up of a separate risk committee to focus on the response to COVID-19. Some board meetings were initially cancelled to allow the Chair, CEO/Principal and Clerk/Secretary to meet prior to rescheduled board meetings. Other boards increased the number of board meetings to deal specifically with issues relating to COVID-19. While some members felt that there may have been an element of ‘information overload’ with the initial increase in frequency of the updates, it was generally acknowledged that this was better than being ill-informed of developments.

Some Chairs highlighted to the Board how moving governing meetings online was a necessary requirement for complying with COVID-19 restrictions and the governors were thanked for their flexibility. During our observations, many board members made comments about the benefit of not having to travel, and others appreciated that online meetings, including committee meetings, could then take place during regular business hours. Some board members acknowledged that they missed some aspects of meeting in person, for example, some commented that it was good to see other ‘humans’, even if it was online, while others joked that they missed the catering facilities. Conversely, some indicated that they missed the ‘human’ element of meeting in person, particularly when members had to mute their microphones and video cameras to allow better internet connectivity when other members were speaking.

Some board members commented that they were able to draw on the existing online learning platforms available to college staff and students and that the expertise of college staff made the transition to online meetings work seamlessly. In addition, boards that had previously been supplied with printed papers seemed to adapt well to accessing them in electronic form. However, there was an indication in the early meetings of certain teething issues, where boards sometimes struggled to find a platform that would be suitable for multiple types of personal devices.

During the meetings themselves, there was a mix of approaches to engaging with the platforms, with some boards asking people to mute their microphones and video cameras to improve connection and avoid interference, while others allowed governors to choose their own preferences for muting. Some Chairs asked governors to use the built-in ‘raise hand’ feature when members wished to speak or when asking for a show of hands for approval, however, often the governors did not use this function and raised their hands in view of the camera, which the Chair sometimes missed.

However, the formality of these practices seemed to mirror each Chair’s usual ‘style’ during in-person meetings, with the Clerk/Secretaries often stepping in to mediate if requests to speak were overlooked, or if the Chair had forgotten to request a show of hands for formal approval. Inevitably, there were often issues with sharing documents online, however, these seemed to be related more to the home broadband speed of the presenter than to any problems with the online meeting platform software.

One other change we observed was that the contact between the executive and the board occurred much more frequently, often on a weekly and even daily basis, to keep members updated as the situation changed during the initial stages of the pandemic. This meant that the focus of the board meetings towards the end of the semester was placed on the response to the pandemic and planning for the coming academic year.

In addition, great concern was given to discussing how the exam results would affect college students. However, by the end of the summer, the board meetings we observed had shifted to focus on assurance: first, that the quality of the student learning experience would be upheld; second, that the executive had acted appropriately to ensure that they had done everything that could be done to preserve the safety of the students and staff; and third, to secure the financial viability of the college.

We have also observed that, while the Chairs strive to maintain the same rhythm of the in-person meetings, by keeping to time and closely monitoring the discussion, some of the more natural qualities of a round-table discussion are lost. For example, during in-person meetings, we often observed private conversations between board members, which often prompted open comments to the wider group. This seemed to have stopped in the online meetings, so some of these collaborative discussions may now be absent or hidden. While there is the opportunity for members to use the ‘Chat’ function in most online platforms, some college boards did not use the function at all. In our previous observations of in-person meetings, these quiet tete-a-tetes were often a way in which the members could test out the waters to gain consensus with at least one other member before contributing to the wider group. This includes quiet discussions that normally take place between key board members, for example, the Chair and Principal/CEO and the Clerk/Secretary. There was some indication, however, in the online meeting observations, that these conversations may have taken place in prior individual meetings, or during the meeting via private messaging services, such as WhatsApp, as some members alluded to having ‘chatted’ before the meeting proper, and it was evident that many members were using other mobile devices during the meeting. In one meeting, in the Chat function, one member had commented on what the speaker was saying and another responded “DM me” (send me a private direct message).

Our Impact Group members have suggested that there is perhaps a need to develop a new protocol for governing online, and governors might be interested in a document developed by the ICSA Chartered Governors Institute, Good Practice for Virtual Board and Committee Meetings. In addition, a member of our research team, Professor Ron Hill, is currently undertaking a study (supported by the College Development Network and the Association of Colleges) on the use of virtual meetings for governing colleges in England and Scotland. The forthcoming report will present governing experience based on questionnaire responses from Board Members, Governance Professionals and Principals gathered from April to July 2020, as well as providing advice for effective virtual governing meetings. You can follow our Twitter feed for updates on the report and its publication.

We are hoping to develop the analysis of our observations further and we welcome any feedback or comments you may have about your experiences of how moving to online meetings has mediated your own governing practices. For anyone wishing to contribute, please contact fe-governing@stir.ac.uk.